Gifts bequeathed to some schools decades ago have generated millions in recent years as fracking unlocks oil and gas reserves.

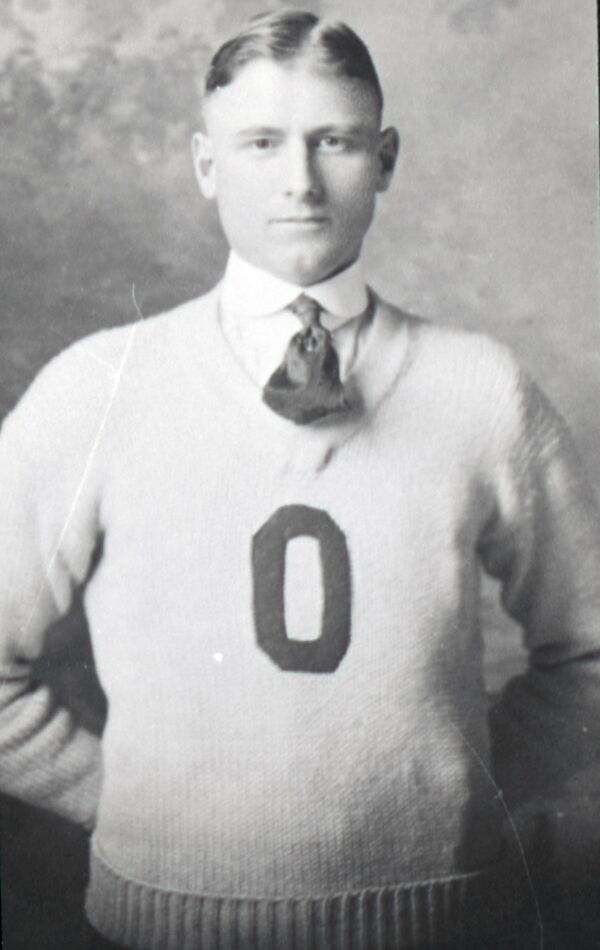

Henry Mosier enrolled in the University of Oklahoma more than a century ago.

He studied pharmacy and competed in track and field, taking second in the hammer throw at a meet hosted by the University of Texas in 1912. After graduating that year, he became a pharmacist in the town of Edmond, north of Oklahoma City. His wife, Ida, worked in a jewelry store. The couple had no children and lived frugal lives. The oil boom was still young, meanwhile. Customers at the pharmacy where Mosier worked shared tips on mineral rights, which he bought as investments.

Mosier died in 1966, bequeathing everything to his wife. She died a decade later, leaving bank accounts, investments, farmland, and mineral rights altogether valued at $1.4 million. Her will left 60 percent of the estate to the University of Oklahoma Foundation. It earmarked 80 percent of that for scholarships for pharmacy students. The rest would aid track athletes.

At the time OU received the gift in 1976, the mineral rights generated about $30,000 a year. According to the foundation’s records, the attorney who handled the estate expected their value to decline as wells were depleted and sealed. Yet the Mosiers’ mineral rights—which are spread all over Oklahoma, including the patch of land in Kingfisher County pictured below and elsewhere in the so-called Scoop and Stack plays—are located in the third-most active area in the U.S. for oil and gas development and acquisition. As hydraulic fracturing unlocked oil and gas reserves, the donation spun more money for OU. Last year the Mosier mineral rights generated $763,000 in cash flow. In 2014, with a lease bonus, they produced $2.35 million.

“Both track and pharmacy have benefited tremendously from the Mosiers’ largesse—and in a way that Henry and Ida could have never imagined,” says Guy Patton, chief executive officer of the University of Oklahoma Foundation, which oversees investments for OU’s $1.1 billion endowment. The donation helps pay tuition for about a third of the school’s pharmacy students and provides the equivalent of full tuition for about 20 members of the 100-strong track team. It’s also funded new buildings including an indoor track facility.

“We didn’t know it at the time, but in the end, minerals were the most valuable part of their gift,” Patton says. “It’s not even close.”

Mineral rights, which can be split from holdings of the surface property, convey ownership of the underground gas, oil, coal, gold, and other natural resources. Unlike land, they don’t require maintenance or payment of property taxes if they aren’t producing. “It’s literally a free option,” Patton says. Altogether, mineral rights have generated more than $30 million for the school’s endowment over the past decade.

While it’s brought newfound wealth, fracking isn’t without controversy. Environmental concerns such as climate change, water pollution, and earthquakes have spurred opposition. Student groups across the country have advocated, mostly unsuccessfully, for their college endowments to divest from fossil-fuel holdings.

At OU, mineral rights have become their own asset class. Most universities aren’t similarly endowed with the right mix of geography and alumni donations. Some institutional investors have found exposure to mineral rights through public and private equity.

Northwestern University, Rice University, and the Mayo Clinic and its pension fund invest in Black Stone Minerals LP, a publicly traded owner of mineral and royalty assets. Rochester, Minnesota-based Mayo’s involvement with mineral rights dates to the mid-1990s, when a grateful patient donated some in Texas, according to Harry Hoffman, treasurer and co-chief investment officer.

The University of Michigan at Ann Arbor has money in four private funds through MAP Royalty Inc., which invests in gas, energy, and solar royalties. Investors are creating more private funds, such as Elm Park Minerals, based in Oklahoma City, which founder and Co-President Kent Regens says recently closed a second fund.

Staff at some universities in oil-rich areas, such as Texas A&M University and Oklahoma State University, oversee new donations and management of mineral rights. The job requires expertise to negotiate leases and ensure royalty checks are placed in the right accounts, which fund hundreds of individual endowments for specific purposes.

OSU’s foundation bolstered its office more than three years ago and now oversees more than 2,000 active wells. The school has acquired rights in 14 states. It’s also amassed estate gifts that may not materialize for years.

Mineral rights run deep in Texas, as they do in Oklahoma.

Take the partnership of Robert Carr and Preston Northrup, whose mineral rights benefited two Texas schools. Carr put down roots about a century ago in Houston, where he worked for various oil companies, leasing and scouting. He and Northrup formed a partnership and later owned minerals under almost 2 million acres in West Texas, most of which would become oil-producing, according to the Carr Scholarship Program.

Northrup made donations to Trinity University in San Antonio, which helped it become the eighth-richest college in Texas. Carr moved to San Angelo, where he became engaged with the public Angelo State University and served as a trustee. After he died in 1978 and his wife died in 1987, they bequeathed all of their mineral rights to the school to provide academic scholarships for “needy and worthy” students.

The mineral portion of their estate, valued at $6.8 million, was expected to decline, says Candice Brewer, who oversees the Carr Scholarship Program at Angelo State. “They felt they were giving us a depleted asset,” she says. “Little did they know, it would be worth $130 million today.” By itself, the Carr Scholarship Program would rank among the top 400 U.S. college endowments.

The scholarship’s interests in 16 West Texas counties generate royalty income from about 50 oil companies each month, bringing in $3 million to $7 million annually depending on oil prices. About half of the almost 10,000 students who attend Angelo State, now part of the Texas Tech system, receive money from Carr scholarships, Brewer says.

The University of Texas holds the third-largest college endowment, just behind Harvard and Yale. Much of its $24 billion is derived from holdings in the Permian Basin ceded to the university by the state of Texas in 1881. Texas A&M, with $10.5 billion, ranks eighth-wealthiest for the same reason.

The recent run of luck at the Texas and Oklahoma schools comes from estates that were settled decades ago.

The estate of actor Erik Rhodes, an OU alumnus originally from Oklahoma City, was bequeathed a quarter-century ago. He starred in a host of Broadway shows and films, including the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers classics The Gay Divorcee and Top Hat.

Rhodes’s estate went to the university after his death in 1990. It included $21,354 in cash and 87 acres of mineral rights that didn’t produce a dime until 2014. “Then we got this phone call,” Patton says. A landman, a contractor hired to investigate title, said OU likely owned the mineral rights that an oil company wanted to lease. These types of transactions provide for an upfront payment that typically lets companies drill for three years, called a lease bonus. Owners receive a percentage of what’s recovered, such as 3/16ths or a quarter, called a royalty. “2014 was a giant year, far and away the largest lease bonuses we’ve ever gotten,” Patton says.

Donations of real estate are often initially more valuable to schools than the minerals. OU, like many universities, typically sells what’s on top, such as homes and ranches, and keeps the mineral rights below. “Technology and price have increased the yield for extraction, and the mineral owner has benefited from that just as the exploration companies have,” says J. Michael Lewis, a partner with Dallas-based Coronado Resources, a limited partnership that invests in mineral rights, and also a member of the Texas Tech investment committee.

OSU, alma mater of oilman T. Boone Pickens, has the third-largest endowment in the state, behind OU and the private University of Tulsa. OSU’s foundation received its first donation of mineral rights in the 1950s. “The foundation started off with very few minerals,” says Robyn Baker, general counsel of OSU’s foundation. “Slowly we began receiving mineral donations, and over the past decade we have seen an explosion in the number of mineral gifts.”

Among OSU’s benefactors: Thomas and Pauline “Polly” Miller of Elk City. The couple met in the 1930s while ballroom dancing, graduated from what later became OSU, and married two years later. He raised broomcorn and cotton on about 800 acres, while she taught home economics, according to a local obituary. They left their minerals to OSU’s foundation after Polly’s death in 1998. Their rights have generated $2 million, with one-third of that coming in the last fiscal year alone. The money goes to scholarships.

Pennsylvania State University, the state’s land-grant school, is also looking to the future. The university often sells real estate that’s donated. However, while Penn State has retained ownership of coal rights, it hadn’t hung on to rights to oil and gas. “We weren’t in this game like other areas of the country,” says Michael Degenhart, assistant vice president for gift planning, who created a program to solicit rights for future royalties.

The Marcellus Shale basin is now the leading source of natural gas in the U.S. While much of the oil drilling along the Marcellus has been curtailed, technological advances can make it valuable for oil again as well, Degenhart says. He and an alumni board have developed a deed for perpetual royalty interests, asking for 2 percent to 5 percent of future royalties.

So far, they have almost a dozen takers. “We’re calling it energy legacy,” he says. “We want to promote gifts through energy wealth.”

Lorin covers endowments at Bloomberg News in New York.

This story is featured in the forthcoming issue of Bloomberg Markets.

SOURCE: Bloomberg.com

About Oklahoma Minerals Founder GIB KNIGHT

Gib Knight is a private oil and gas investor and consultant, providing clients advanced analytics and building innovative visual business intelligence solutions to visualize the results, across a broad spectrum of regulatory filings and production data in Oklahoma and Texas. He is the founder of OklahomaMinerals.com, an online resource designed for mineral owners in Oklahoma.